The Echoes of Cowboy Carter on Renaissance: Zooming out and Tapping In

Medium-processed thoughts on the relationship between Beyoncé's Act I and Act II

The Echoes of Cowboy Carter on Renaissance: Zooming out and Tapping In

I don’t listen to music based on what’s trending. Some albums just have me locked in, sometimes for years. Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter and Renaissance are sumptuous, onion-like albums, I keep returning to. I began to understand (some of) the intention behind the flow from one album to the next. The transition portal has captured me. Because Cowboy Carter was initially designed to be Act I, but flipped the release order after the earth flipped the script on humanity by dropping COVID-19 first! Nevertheless, it would be fun to re-listen to Renaissance (Renny) as if it follows Cowboy Carter's (CC) context. These are a series of medium-processed thoughts regarding some of the echoes of the Cowboy Carter album that we hear across Renaissance.

Beyoncé is very intentional with her art, so the acts of this trilogy are designed to complement and speak to each other. That said, I have a few thoughts that zoom out on the transition from CC to Renny. This is about how the albums relate to each other in terms of what is being communicated: playing with masculinity, legacy, blackness, looking beyond America, and the transformative potentials of the feminine. It is not an album review.

Please don’t drag me if you feel I’ve missed obvious stuff, didn’t cite scholarship, or you think about it differently. Instead, tell me what you think, add to the ideas, or blow my mind. Just be nice.

A Masculine Character:

There were three things I clocked immediately on my first listen of Cowboy Carter:

The dissertation-level construction of the album, including ‘American Requiem’ as an introductory chapter and thesis/positionality statement

That ‘Alligator Tears’ was about white American self-victimization whilst actively playing the villain.

That there is a lot of masculine energy in many of the songs, and slips into traditionally masculine roleplay and posturing.

Let’s talk about it.

First, it goes without saying that though Beyoncé identifies as a woman, the album is titled Cowboy Carter. It’s less about the name she married into than disrupting and re-positioning a genre legacy deemed to have originated with the (white) Carter family. Surprise! They were exploiting and profiting off of a Black man’s (Leslie Riddle) work and artistry. It’s unsurprising since that’s been America’s entire steez for centuries; it’s in the DNA.

Anyway, the ‘cowboy’ angle references Black men as the original cowboys, wh were ranch hands. The ‘boy’ was meant to demean and racially infantilise, as white men were referred to as ‘cowhands’. The term cowboy evolved to be synonymous in the Western film genre with a disrupter who doesn’t play by the rules but has a code (‘Spaghettii’, anyone?). As an insult, it means a rogue or trickster. So, there is already a masculine foundation established in the album title. Beyoncé uses ‘cowboy’ in multiple forms in order to get everything she came for on this album.

It's not necessary to be a man to embody or portray masculine energy (we all have at least a little bit of testosterone in us). So, please don’t mistake what I am saying (and forgive me for any pronoun errors). Many songs offer more of Bey’s feminine (or even non-gender conforming!) side. However, songs like ‘Protector,’ ‘Bodyguard,’ and ‘Just For Fun’ exude masculine role association but juxtaposed with feminine experiences. ‘American Requiem’ and ‘Spaghettii’, too, can be argued tonally and story-wise that they are from a masculine perspective.

Most importantly, Cowboy Carter is a heroic, Black Southern figure. Perhaps he was sent by the Ancestors. He is taking a lay of the land of his people and does not like the injustice he sees. He arrives, pursuing truth and covered in ‘peace and love, y’all’.

But the more he observes, the longer he stays, the more pissed Cowboy Carter gets at the conditions. Sometimes, he gets violent and breaks the rules when disrespected (‘Daughter’—turns into the father when crossed; on ‘Spaghettii’ CC--becomes an outlaw). Towards the end, the ‘Buckiin’ ‘Tyrant’ strikes a proverbial match and lights up the juke joint.

Cowboy Carter’s Birth and Death: The Beyoncé Bowl

Herby Revolus has a YouTube and Patreon where they sometimes discuss Beyoncé’s work. They are brilliant, hilarious, and for the gworls. Herby discusses Cowboy Carter as a masculine figure who turns vengeful and violent sometimes. Theirs is the most thorough treatment I’ve seen so far of this idea. The CC figure dies at the end of the album, which comes across on ‘Amen’. Herby reinforces this death in his (now removed) video about the Beyoncé Bowl by noting Cowboy Carter’s ascension to death ending in a ‘Bang’.

Let’s recall that the CC album dropped on the 29th of March, Good Friday (aka the day of Jesus’ crucifixion).

Even more interesting is the symmetry in Bey’s live performance. You need to have a birth for a death. And there is one. Where we ascend in death, we descend at the beginning for the birth. The camera starts in the sky and then pans down to the tunnel of NRG stadium. We see Beyoncé being led on horseback, travelling through a tunnel, singing about ’16 Carriages’ on a ’long black road’. The tunnel we see her in is the birth canal, and she emerges from it via a blinding white light after being told to ‘arise’ by a chorus of Blackbirds. This is the birth of Cowboy Carter, and we see Beyoncé remove her hat and change her facial expression to a very determined, mission-oriented one as she walks into the light. Cowboy Carter emerges in Chaps, singing an ass-shaking treatise about keeping the faith amid strife in America. Cowboy Carter departs on a song with similar themes because ‘Texas Hold’ Em’ is about small pleasures amidst surviving turbulent environmental (heatwave, tornado, freezing temps) realities.

Bey-Z (@beyzhive) predicted and anticipated Bey performing ’16 Carriages’ for Christmas day because of its religious nods to the story of Jesus’ birth. They (unsure of pronouns) have very clever Twitter threads. You can visit them for more on this and religious/art historian breakdowns of Renaissance/Renaissance imagery because that’s beyond my skillset. The point to take away is that this ‘holy’ birth of the Cowboy Carter figure is deliberately being likened to a hero or saviour-type with qualities similar to the biblical Jesus. We’ll return to birth (re-birth) later when I get into Renaissance (Femininity, Love, and Freedom section).

One more significant piece of symbolism from the Beyoncé Bowl is the red and white ‘road’ we see Beyoncé travel (the same red and white that appears in the flag on the album). Beyoncé walks on the narrow red line throughout the performance, surrounded by broader swaths of white. White can be a symbol of innocence, celebration, and death/mourning. The performance encompasses all those symbols. In traditional Western films, white hats symbolise the good guys, and we see Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter wearing an extra-large one.

But the Red. The Red. The ‘Red Road’ is a First Nation metaphor for living a spiritual way of life governed by purpose and commitment, an internal obligation. A person who walks the Red Road, is walking in the right direction in a good way even if the path is difficult. There are seven sacred virtues that guide them you on that path

The idea of the Red vs the Black Road concept as evidenced in the Beyoncé Bowl was brought to my attention by yoyo (@yoyojos). The Black Road is wider and easier to follow at first. But as things become challenging, and it becomes harder to keep the faith (‘we gotta keep the faith’), people drop off (‘day ones have been telling me that they won’t be around/right about now’). The Red Road is narrower and lonelier but more rewarding to those with a deep commitment to faith and integrity. The Red Road is the hero’s journey. And Cowboy Carter is what? Exhaaaccly.

That doesn’t mean Cowboy Carter suffers fools on this road. Though the 14th of January 2025 announcement is delayed, something tells me the bold, red font aligns with being a White Hat following the Red Road.

With all of this talk about masculinity and heroism, it would be a shame for you to think the Cowboy Carter figure is a man. No, it’s a character that leans into masculine (and sometimes feminine) tropes, depending on what tool is needed in the circumstance.

Past, Present, and Afro-Future legacy:

One thing about Beyoncé—she is a student of history. A woman who understands that ‘the past and the future merge to meet us here’. Structurally, on Cowboy Carter, this concept is represented. Guided by legends of Country music’s past (Willy Nelson, Linda Martell, Dolly Parton), the album is split in to thirds. The latter part is the Chitlin’ Rodeo Circuit which leans on Black country experiences. It informs what Afrofuturism of the genre could sound like if the Albino Alligators of the industry weren’t so damn intransigent about the concept of this genre and Black people’s foundational role in it.

In this latter part of the album, we revel in possibilities that are not necessarily linear in structure or lean in their sound, where femininity and love peak through (‘Desert Eagle’, ‘Riiverdance’, ‘II Hands II Heaven’, ‘Sweet*Honey*Buckiin’). Largely full of bangers that push the limits of instruments and concepts associated with country, this final part of the album is an earthly portal to the futuristic Renaissance dimension. Had Cowboy Carter come first, we would be getting ready without knowing we were getting ready. Lost in the border-defying possibilities of Black Country on the American plain, we leave the country with Cowboy Carter at the end of ‘Amen. Lifted up, we are raised, projected toward Planet Renaissance. It is a place free from many of the constraints Cowboy Carter encountered during their American journey.

From America to Infinity and Beyond:

Many folks have already noticed that, as the conclusion to Cowboy Carter, ‘Amen’ transitions neatly into Renaissance. There’s no argument about it: narratively and sonically, we are being teleported, ascending to the Renny dimension at the end of ‘Amen’.

I’ve already discussed above that the Rodeo Chitlin’ Circuitry of the album’s last third begins musically shifting our minds, bodies, and expectations by using Black Southernness to (re) elasticise the American country genre. It is only after that preparation, and with the death of Cowboy Carter that we can find new salvation and build our own foundations in another dimension. It's a dimension that is antithetical to the colonial, binary ideas that have held us in a chokehold for too long (more in the Femininity, Love and Freedom section).

This a reminder

In Christianity (which is very influential to this album), salvation is only made possible after the sacrificial death of the Jesus figure and his re-birth. Cowboy Carter asks for mercy at the beginning of ‘Amen’ and remarks on how he can see that we are hurting badly. Does this not remind you of Jesus’ pleas on the cross? CC is dying and takes time to acknowledge our pain (‘Mercy on me…I can see you hurting badly’) and reiterate his original message.

A house built on the blood and bodies of his people cannot stand. Statues made of idealised lies get torn asunder. And since the house Black people built but never settled in (because it’s inhospitable and needs to undergo renovation),

We can move on, even if it’s just in spirit.

With the re-election of Trump, ‘Ame(rica)n Requiem’ is here, so say a prayer for what has been. Cowboy Carter cannot get justice in a land full of Philistines because justice isn’t to be found. We are moving upward and onward, taking flight in the dark black night to a place where Cowboy Carter’s re-birth is manifested as Renny (or Venus as I will refer to her). The transition from ‘Amen’ to ‘I’m That Girl’ captures this sense of flight.

Let’s zoom out on the idea of taking flight as a means of escape. When the album first debuted, Beyoncé used the word ‘escape’ to describe what the Renaissance album was meant to provide us and what it provided her. As an escape from oppression, flight has been a central pillar of Black American culture, extending back to slavery. Writers and artists continued to reinterpret the concept to convey a longing for freedom and reconciliation not possible in the land of our captors.

Femininity, Love and Freedom: Renny’s M.O.

Do we not hear the alien-like, space-like intonations at the start of ‘I’m that girl’? Tap into this other dimension! CC goes home (‘I’m coming home, I’m coming hoooOme’) not to his Father’s house where there are many mansions (extending the metaphor of Christ), but to the Motherland…or the Motherboard where he is reprogrammed (rebirthed) as a femme-forward figure I call Venus. If the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost are parts of one complete entity, then so are Cowboy Carter, Renny (Venus) and Act III

Back to Venus. She is ‘that girl’ not because of the clothes she wears or how good she looks. Not the way she stands, the diamonds she wears, nor her man. It’s just that… she’s that girl. And that’s on the periodic table. As the second planet from the sun, she is solar-genic (‘from the top of the morning I shine’). It’s a power she didn’t want, and everything next to her is lit up, too (raaah). She’s an indecent freak on the weekend. A heathen ready to dive into the deep end. ‘I’m that girl’ sets up the main themes for what this other planetary dimension of Renaissance will bring. Let us be-gin.

Renny has a clear lean toward femininity, which is different from the more masculine-forward Cowboy Carter figure. Much like masculinity, this album's overt feminine and queer expressions aren’t bound to a singularly gendered body. On Venus, we are off that shit. We connect with our bodies, other people’s bodies, and souls. Both femininity and queer expressions have been maligned, devalued, and suppressed in Western civilisation (understatement, I know). It’s no accident that Beyoncé encourages us to revel in queer possibilities. I mean, we’ve entered another dimension where those old codes do not bind us.

One of my favourite things about Beyoncé is that she is a lover girl, boots (spurs). Pop songs visit the topic of love so often that attempts to discuss it can seem trite. And we do not treat ‘love’ as a worthwhile topic of exploration: something that is intricately linked to heavier topics of freedom, resistance, and bodily autonomy as throughlines in blackness. One of the biggest reasons is that we associate ‘love’ with the feminine. In her infinite wisdom, Motherboard Yoncé as Venus gives us femininity galore on Renaissance. Through queer, feminine salvation, we can build new foundations and write new rules.

Cowboy Carter could not get justice for his people in America because it is a land without love for those people. Renaissance focuses on love as the foundation and the possibilities we gain through that. Possibilities like:

· Sexual expression without shame

· Reconciliation of mind and body with no concern for gender binaries

· Joy and movement without religious judgment

· Community and purpose outside of capitalism

· Genuine connection, through vulnerability, with another person

What better way to drive these themes home than using Black, queer musical expressions of Disco and House? The former was deliberately ushered out for its queer-leaning ways, especially on the eve of a return to conservative hypermasculinity in the Regan era.

Bigger than America

In 2022, when I first heard the repeated use of ‘un-American life’ on ‘I’m that girl’, I knew it was important but did not understand the full context (perhaps I still don’t). I knew then that it at least references a ‘Double Consciousness’ (W.E.B. Dubois) sense of being both a Negro and an American, and that these are at war with each other. Having built a country but constantly told you don’t belong there is dispossessing. It's kind of like originating the country sound and then being audaciously told you’re not country (lol). Leaning into an ‘un-American life’ means leaning into a Negro-ness without borders, if you will. Renny does that. Now, having the context of Cowboy Carter, un-American also refers to a life that is bigger and beyond the constraints of America itself. Renny highlights this: the only American artists *featured* as performers on the album are either LiGaBigaTiQIA (Big Freida, T.S. Madison) Americans or diasporic Black folk (Beam, Tems, Grace Jones). They are all ‘un-American’ in some way.

The Black Venus/Aphrodite of it all

We travel to Venus (and wake up in Mars?) to consider liberatory explorations of beingness and love. But why Venus? I am, of course, assigning this name based on Beyoncé’s portrayal of Venus de Medici (or Aphrodite as the Greeks called her) in the Renaissance World Tour.

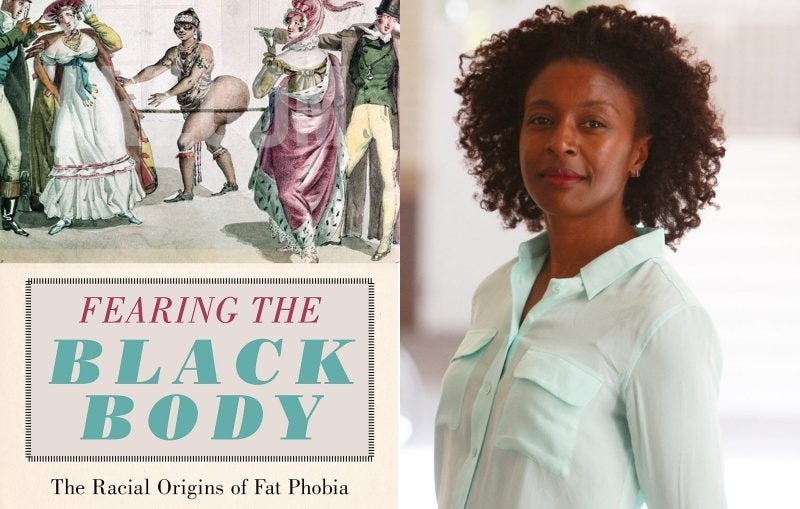

During The Renaissance (15th-17th century), Venus became the pinnacle of female beauty to which real women’s bodies should measure up. Artists, poets, and thinkers at the time were obsessed with aesthetics, especially in the female form. As the goddess of love and beauty, Venus—as the ideal for white women—reigned long until “race science” became the rage in the early 19th century. By the middle of the 1800s, Venus was considered a bit pudgy for American [white] women to fashion themselves after. Slenderness was inseparable from whiteness in America as a requirement to be considered beautiful or even a patriotic ‘Anglo-Saxon’. Bear with me for a second; I promise this relates to Beyoncé’s embodiment of Venus on Renaissance.

An ‘African Venus’ was also portrayed in the 16th century. European artists like Titian, Mantegna, and Veronese began reimagining antiquated stories, including biblical ones, by inserting Black women into them. But it was always from a position of service to aristocratic white women.

This made it clear that although African women were capable of a type of beauty, theirs was inferior to European women because the African Venus was more muscular, lacked shame, and her desirability was only for sex, never qualifying for love. Only Venus Pudica (the pure, modest, white one) could be the goddess of Love.

I wrote all of that because when Beyoncé tells you she is a clever girl and that no one else can think like her, it’s not hubris.

Building her own foundation a century after her people did the same during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, Beyoncé carries on that tradition by inverting the original European Renaissance. She reappropriates Venus’ identity and iconography of ‘The Birth of Venus’, which is most evident during the Renaissance World Tour.

The demure (black!) hands, half covering private parts, are painted onto an unabashedly sexy catsuit. Beyoncé deliberately castrates the sex/purity binary by mushing them together and creating a new standard. This is femininity in contradiction. This is precisely the point of Renaissance. Beyoncé centres Black femininity as the goddess of Love and an advocate for sexual desire and joy through dancing. Celebrating all bodies as beautiful, including the Thique ones for which African women have been maligned since the 18th century, Beyoncé, as Venus, revels in her Black body.

[BIRTH OF VENUS AND LA PRIMAVERA BY BOTTICELLI]

For Renny, Beyoncé also draws on another Botticelli painting of Venus, which came before ‘The Birth of Venus’. It’s called ‘La Primavera’, which gives Eve-in-the-garden-of-Eden tees. In it, Venus dances joyously, revelling in nature’s beauty and bounty of fruits. Nymphs and gods surround her.

In the mid-19th century era of race-making in American, Anglo-Saxon superiority was influenced by Protestant reform, which emphasised temperance (denial) and women were the targets of this instruction because healthy women’s bodies were critical to the future of the white race (sound familiar?). Feminine aesthetics were being advocated away from the European Venus, who was suddenly too short, ugly, and round to fit the new (American) ideals. This makes “my un-American life” even more resonant. Beyonce refuses to be governed by the changing whims of white feminine aesthetics.

If Venus Pudica was the goddess of love and beauty, African Venus birthed all of civilisation. Beyoncé’s Venus re-births us into a dimension where we are the standard for beauty, love, joy, and unashamed in our sexual desires.

Concluding thoughts

I do not know what Act III will bring, but I will be back to examine the transition from Renaissance and how Cowboy Carter informs the third act. Herby Revolus mentioned that they think Beyoncé is too obsessed with the number 4 for her not to bless us with an Act IV. I agree, but I think it’s not an album but a film. The film will likely reveal the story that runs through all three sonic masterpieces. I doubt it will follow the chronological flow of the albums. It could reveal another story puzzle that can only be apparent once all three acts are available.

On that note, by 2026 (2027 at the latest), a top-tier university (do not read as white) better come up off an honorary doctorate for Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter. She has been engaged in this scholarly work of an unprecedented quality for a musical artist. Scholarship is about deep thinking and pulling together threads, not using a bunch of jargon to justify an industry. It’s time. Stop playing with Beyoncé and give her her things!

I just know there has to be a coven of Blackademics with a draft book proposal just waiting on Act III to drop so they can circulate it to publishers. À la The Lemonade Reader, the Genre Trilogy will be a thique volume about the scholarship running across Acts 1-3. Don’t leave me out of that volume, a beg!

This became too long to list the lyrical similarities I picked up across both albums. I’ll do that on the next post. I hope this piece was entertaining and informative. EYE enjoyed writing it, and that’s the point of this blog. I just want to nerd out on stuff I can’t stop thinking about, thus making it my number one feeling. This post began as fragmented thoughts for a Twitter Spaces that didn’t happen due to unforeseen circumstances. I thought, minus well [sic] do something with it. A special thank you for @isagenius and @yoyojos for the motivation, retrieving photos for me, providing ideas I could run with, and for listening to my ideas and lending your own.

What do you want to add about the Cowboy Carter-fication of Renaissance?

Subscribe for more thoughtful and fun writing!

Check out my April 2024 article about the decided Blackness of ’s ‘Jolene’.